When Was Jesus Really Born?

Dave Roos

77–97 minutes

Around the world, Christians anxiously await the arrival of Christmas, a joyous day to celebrate the birth of Jesus. But more than two millennia after Jesus’ momentous ministry, even Christians can’t agree on his birthday. In Catholic and Protestant traditions, Christmas is celebrated Dec. 25, while Orthodox Christians in countries like Russia, Greece and Egypt celebrate Christmas on Jan. 6 or 7.

Yet according to historians and biblical scholars, even those traditional dates are debatable. The Bible’s most detailed account of the Nativity is in the New Testament’s Gospel of Luke, but even that “orderly” narrative — complete with highly specific references to Roman rulers and a worldwide census — fails to name a day, month or even a year for Jesus’ birth.

“We have this modern obsession with dates and chronological order, but the gospel writers were much more interested in theology than chronology,” says Ian Paul, a theologian, biblical scholar and author who blogs at his website Psephizo.

That said, Paul’s own best guess for the true date of Jesus’ birth is somewhere in September, based on a complex set of calculations related to the birth of John the Baptist, also mentioned in Luke. A fall date for Christmas makes sense when you consider that the shepherds were in the fields tending their flocks, a sign of mild weather. Paul says that by December, the Judean foothills outside of Bethlehem are cold enough to get snow.

Ultimately, whether Jesus was born in December, September or March doesn’t change the true meaning of Christmas, but the debate over Jesus’ “real” birthday shows just how difficult it is to place specific dates on ancient events.

Contents

- Jesus Wasn’t Born in ‘Year 1’

- How December and January Became the Traditional Dates for Christmas

- The September Theory of Christmas

Jesus Wasn’t Born in ‘Year 1’

Before we even get to the month and day debate, historians generally agree that we’ve got the year of Jesus’ birth all wrong. How can that be, though, if “year 1” on the Gregorian calendar was based on the year that Jesus was born?

The short answer is that the man who invented the idea of anno Domini (shortened to A.D.) for “Year of Our Lord” was off by several years. Even Pope Benedict XVI agreed in a 2012 book that Dionysius Exiguus, the sixth-century monk who first calculated the year of Jesus’ birth, miscounted, and that Jesus was likely born anywhere between 7 B.C. and 2 B.C. (Modern writers may use C.E. in place of A.D. and B.C.E. in place of B.C., to be religiously neutral.)

One compelling reason for an earlier birth year is that the Bible mentions in several places that Jesus was born when Herod the Great was king of Judea. But Herod the Great supposedly died in 4 B.C.E., according to Flavius Josephus, the famed Roman-Jewish historian who lived in the first century C.E. If we take Josephus’s word for it, then Jesus must have been born at least four years earlier (and probably more) than our calendar says.

How December and January Became the Traditional Dates for Christmas

The popular theory that Christians chose Dec. 25 to co-opt the pagan solstice festival of Sol Invictus is not based on strong evidence, but rather on the margin scribblings of an unnamed Syrian monk in the 12th century. Rather than accusing Christians of stealing the holiday, he was offering a theory for why western churches “moved” Christmas from January to December.

In fact, the first mention of a date for Christmas was around 200 C.E., and the earliest celebrations of it were 250-300, “a period when Christians were not borrowing heavily from pagan traditions of such an obvious character,” according to the Biblical Archaeology Society.

For centuries after Jesus’ death, early Christians didn’t pay much attention to his birthday. In those days, Christians were persecuted and even martyred for their faith, which led them to put an emphasis on Easter, when Jesus himself was martyred on the cross, but overcame death and was resurrected.

It wasn’t until the third and fourth centuries C.E. that early Christian theologians put forth possible dates for Jesus’ birth. And even then, those dates were related to Easter. In ancient times, Paul says, there were traditions that the lives of great men were connected to specific times of year. Heroic figures often died in the same month and on the same day that they were born (years apart of course). In Jesus’ case, it looks like ancient sources believed that he was either born or divinely conceived during Passover, the springtime Jewish holiday during which Jesus was later crucified.

Christians who believed that Jesus was conceived around the time of Passover/Easter counted nine months ahead to identify his birthday. In Rome and other western locales, they calculated Passover in the year that Jesus died as occurring March 25. In eastern Christian communities, they used a Greek calendar that placed that same Passover on April 6. Add nine months and that’s how Christianity came up with two traditional dates for Christmas: Dec. 25 and Jan. 6.

The September Theory of Christmas

So why do biblical scholars like Ian Paul believe that the true date for Christmas ought to be in September? It comes from a close reading of the clues left behind in Luke, particularly what the gospel’s authors have to say about the timing of the birth of John the Baptist in relation to Jesus.

Luke’s version of the Christmas story doesn’t begin with Mary and Joseph, but with another couple, Elizabeth and Zechariah, who were old and childless. Zechariah was a priest in the Temple, and one day the angel Gabriel appeared to him in the Temple and told Zechariah that his wife would bear a son named John who would prepare the world for the coming of the Lord. Zechariah doubted Gabriel’s message and was struck dumb. But when his service in the Temple was over, Zechariah went home and Elizabeth soon became pregnant.

What does this story have to do with Jesus? The angel Gabriel also visited Mary and told her that Mary was going to conceive and give birth to Jesus, the Son of God, even though she was a virgin. Luke tells us that this second visitation to Mary happened “in the sixth month of Elizabeth’s pregnancy.”

With that key fact, it’s possible to deduce that Jesus was conceived six months after John was conceived. But that only helps us if we know when exactly John was conceived. And how would we know that?

Again, the Bible provides more clues. Luke tells us that Zechariah “belonged to the priestly division of Abijah.” Each division of priests took turns performing sacrifices and other services in the Temple. In 1 Chronicles 24, the order of Temple service is laid out by divisions numbering one through 24, with Abijah listed as eight in the rotation.

As Paul calculated on his blog, if each priestly division served for one week with the first week of the ecclesiastical calendar landing in late March, that would put Zechariah in the Temple in early June. If Elizabeth conceived soon after the angel visited Zechariah in the Temple, and Mary conceived six months later, then it places Jesus’ birth in September of the following year.

Paul likes the September theory of Christmas for several reasons, including the shepherd idea mentioned above. Would Luke have placed shepherds in the fields if it was the middle of winter?

But there are also some holes in this theory. The biggest problem is that each priestly division served more than once a year in the Temple. What if Gabriel appeared to Zechariah during his second stint in the temple six months later? That would place Jesus’ birth in March, which Paul admits is a distinct possibility.

Thomas Wayment is a professor of classical studies at Brigham Young University who has written about the competing theories regarding the timing of Jesus’ birth. He finds that the debate over Jesus’ birthday is intellectually fascinating and worthy of discussion but misses the point spiritually.

“Maybe, just maybe, we’re better leaving it open in a sense,” he says. He has seen early Christian references to Jesus’ birth in April and May in addition to December and January. “We’re celebrating an event, not a day.”

St. Francis Is Credited With Creating the First Nativity Scene in 1223

By: Vanessa Corcoran

Around the Christmas season, it is common to see a display of the Nativity scene: a small manger with the baby Jesus and his family, shepherds, the three wise men believed to have visited Jesus after his birth and several barnyard animals.

One might ask, what are the origins of this tradition?

Contents

- Biblical Description

- Start of Nativity Scenes

- Nativity Imagery in Art

- Political Turn of Nativity Scenes

Biblical Description

The earliest biblical descriptions, the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke, written between A.D. 80 and 100, offer details of Jesus’ birth, including that he was born in Bethlehem during the reign of King Herod.

The Gospel of Luke says that when the shepherds went to Bethlehem, they “found Mary and Joseph, and the baby, who was lying in the manger.” Matthew tells the story of the three wise men, or Magi, who “fell down” in worship and offered gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

But as my research on the relationship between the New Testament and the development of popular Christian traditions shows, the earliest biblical descriptions do not mention the presence of any animals. Animals first start to appear in religious texts around the seventh century.

A series of early Christian stories that informed popular religious devotion, including what’s known as the Infancy Gospel of Matthew, attempted to fill in the gap between Christ’s infancy and the beginning of his public ministry. This text was the first to mention the presence of animals at Jesus’ birth. It described how the “most blessed Mary went forth out of the cave and entering a stable, placed the child in the stall, and the ox and the ass adored Him.”

This description, subsequently cited in several medieval Christian texts, created the Christmas story popular today.

Start of Nativity Scenes

But the Nativity scene now re-created in town squares and churches worldwide was originally conceived by St. Francis of Assisi.

Much of what scholars know about Francis comes from “Life of St. Francis,” written by the 13th-century theologian and philosopher St. Bonaventure.

Francis was born into a merchant family in the Umbrian town of Assisi, in modern-day Italy, around 1181. But Francis rejected his family wealth early in his life and cast off his garments in the public square.

In 1209, he founded the mendicant order of the Franciscans, a religious group that dedicated themselves to works of charity. Today, Franciscans minister by serving the material and spiritual needs of the poor and socially marginalized.

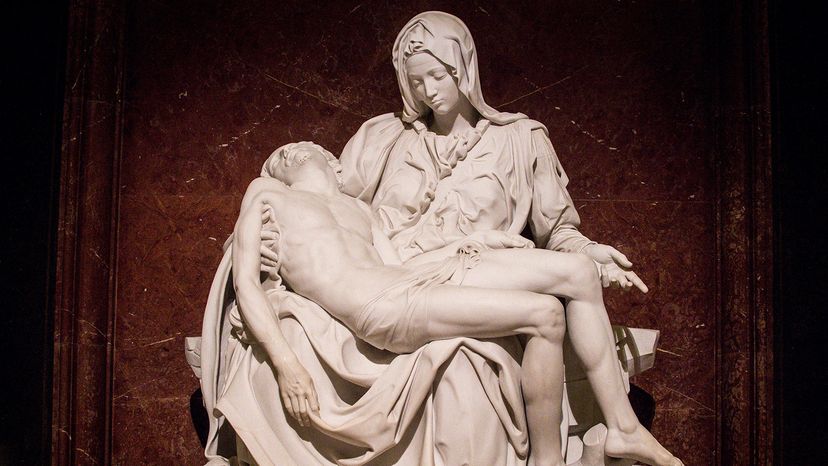

According to Bonaventure, Francis in 1223 sought permission from Pope Honorius III to do something “for the kindling of devotion” to the birth of Christ. As part of his preparations, Francis “made ready a manger, and bade hay, together with an ox and an ass,” in the small Italian town of Greccio.

One witness, among the crowd that gathered for this event, reported that Francis included a carved doll that cried tears of joy and “seemed to be awakened from sleep when the blessed Father Francis embraced Him in both arms.”

This miracle of the crying doll moved all who were present, Bonaventure writes. But Francis made another miracle happen, too: The hay that the child lay in healed sick animals and protected people from disease.

Nativity Imagery in Art

The Nativity story continued to expand within Christian devotional culture well after Francis’ death. In 1291, Pope Nicholas IV, the first Franciscan pope, ordered that a permanent Nativity scene be erected at Santa Maria Maggiore, the largest church dedicated to the Virgin Mary in Rome.

Nativity imagery dominated Renaissance art.

This first living Nativity scene, which was famously depicted by Italian Renaissance painter Giotto di Bondone in the Arena Chapel of Padua, Italy, ushered in a new tradition of staging the birth of Christ.

In the tondo, a circular painting of the Adoration of the Magi by 15th-century painters Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi, not only are there sheep, a donkey, a cow and an ox, there is even a colorful peacock that peers over the top of the manger to catch a glimpse of Jesus.

Political Turn of Nativity Scenes

After the birth of Jesus, King Herod, feeling as though his power was threatened by Jesus, ordered the execution of all boys under 2 years old. Jesus, Mary and Joseph were forced to flee to Egypt.

In an acknowledgment that Jesus, Mary and Joseph were refugees themselves, in recent years, some churches have used their Nativity scenes as a form of political activism to comment on the need for immigrant justice. Specifically, these “protest nativities” have criticized President Donald Trump’s 2018 executive order on family separation at the U.S.-Mexico border.

For example, in 2018, a church in Dedham, Massachusetts, placed baby Jesus, representing immigrant children, in a cage. In 2019, at Claremont United Methodist Church in California, Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus were all placed in separate barbed-wire cages in their outdoor Nativity scene.

These displays, which call attention to the plight of immigrants and asylum seekers, bring the Christian tradition into the 21st century.

Vanessa Corcoran is an adjunct professor of history and an academic counselor at Georgetown University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. You can find the original article here.

How Christmas Works

By: Sarah Dowdey | Updated: Dec 3, 2021

The first harbingers of Christmas arrive in October when jarring sales and decorations follow fast on the heels of summer. But by December, Christmas’s true heralds are out: twinkling lights lining streets, the smell of balsam and gingerbread cookies wafting through the house, and visiting friends and relatives pile into ever room of your house. The season’s spirit drives people to the mall, to the kitchen, to midnight mass and to festive gatherings.

But how did people celebrate Christmas before the advent of shopping malls and electric lights? What’s the history behind the tradition? At its core, Christmas is a celebration of the birth of Jesus. The holiday’s connection to Christ is obvious through its Old English root of “Cristes maesse” or Christ’s Mass. For Christians, it is the time to renew one’s faith, give generously and consider the past.

But Christmas is also a secular celebration of family — one that many non-practicing Christians and people of other religions are comfortable accepting as their own. The secular nature of Christmas was officially acknowledged in 1870 when the United States Congress made it a federal holiday. Federal and state employees and most private businesses observe Dec. 25 by not working.

Christmas is also a fascinating miscellany of traditions: one that combines pre-Christian pagan rituals with modern traditions. Every family that celebrates Christmas has its own customs, some surprisingly universal, others entirely unique — but all comfortably familiar in their seeming antiquity.

In this article, we’ll learn about the history of Christmas from its pagan roots to its modern incarnation as a shopping blitz.

Contents

History of Christmas

It would be easy enough to imagine Christmas as a simple continuum of tradition dating from the birth of Christ. You’d begin with the nativity story, apply the Dec. 25 date to Jesus’ birth, establish the gift-giving precedent of the magi and work from there. Over the centuries, classic Christmas traditions would accumulate: perhaps beginning with the yule log, followed by the Christmas tree and finally winding up in the present day with giant inflatable snowmen and icicle lights.

The history of Christmas, however, is hardly a continuum. It is a varied and riotous story, one that actually predates the birth of Christ. Early Europeans marked the year’s longest night — the winter solstice — as the beginning of longer days and the rebirth of the sun. They slaughtered livestock that could not be kept through the winter and feasted from late December through January. German pagans honored Oden, a frightening god who flew over settlements at night, blessing some people and cursing others. The Norse in Scandinavia celebrated yuletide, and each family burnt a giant log and feasted until it turned to ash.

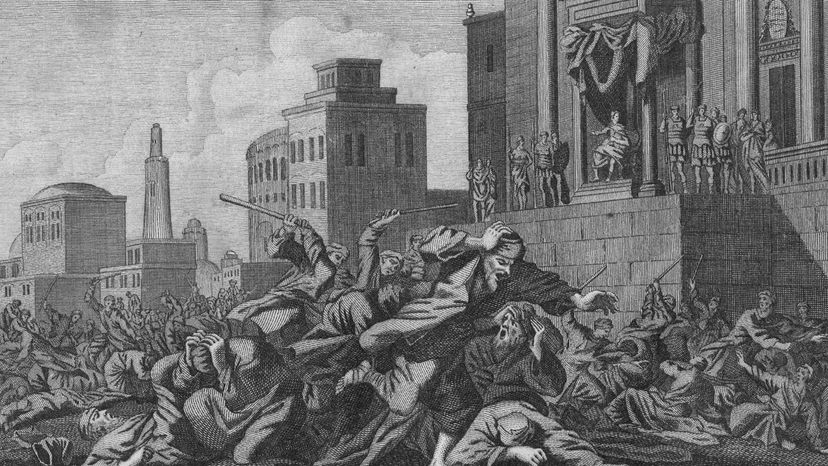

In Rome, people celebrated the raucous festival of Saturnalia from Dec. 17 to Dec. 24 in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture. The celebration consisted of a carnival-like period of feasting, carousing, gambling, gift-giving and upended social positions. Enslaved people could don their masters’ clothes and refuse orders and children had command over adults. Two other Roman festivals, Juvenalia, a feast in honor of Rome’s children, and Mithras, a celebration in honor of the infant god Mithra, also fell near the solstice.

By the fourth century, the church decided that Christians needed a December holiday to rival solstice celebrations. Church leaders selected Dec. 25 for the Feast of the Nativity. Christmas gained ground over the next several hundred years, becoming a full-fledged holiday by the ninth century, although it was still less important than Good Friday and Easter.

Early Christmas, however, was not the peaceful, albeit busy family holiday we know today. Christmas’ proximity to Saturnalia resulted in it its absorbing some of the Roman festival’s excesses. Christmas in the Middle Ages featured feasting, drinking, riotous behavior and caroling for money. Religious puritans disapproved of such excess in the name of Christ and considered the holiday blasphemous. Oliver Cromwell went so far as to cancel Christmas when he seized control of England in 1645. Decorations were forbidden and soldiers patrolled the street in search of celebrants cooking meat. Puritans in the American colonies took a similarly dour view of Christmas: Yuletide festivities were outlawed in Boston from 1659 through 1681.

But by the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, Christmas began to take on the tame associations it has today. New Yorker Washington Irving wrote popular stories about Christmas that invented and appropriated old traditions, presenting them as the customs of the English gentry. Queen Victoria’s German husband, Prince Albert, introduced a Christmas tree to Windsor Castle in 1846. An engraving of the couple with their children in front of the tree popularized the custom throughout England and the United States.

Christmas Gifts

For many people — whether they care to admit it or not — Christmas is about presents. Children nearly burst in anticipation of Christmas morning. Far-sighted adults start stockpiling on-sale gifts early in the summer. The procrastinating multitudes flock to the mall in the week preceding the holiday. Americans spent over $$789.4 billion billion on gifts in 2020, according to the National Retail Federation. That includes retail and online sales.

Christmas’s gift-giving tradition has its roots in the Three Kings’ offerings to the infant Jesus. The magi traveled to Bethlehem to present Christ gifts. Some Eastern Orthodox Churches and European countries still celebrate the traditional date of the Magi’s arrival — Jan. 6 or Three Kings’ Day — with a Christmas-like gift exchange.

Romans traded gifts during Saturnalia, and 13th century French nuns distributed presents to the poor on St. Nicholas’ Eve. However, gift-giving did not become the central Christmas tradition it is today until the late 18th century.

Gifts were ostensibly meant to remind people of the magi’s offerings to Jesus and of God’s gift of Christ to humankind. But despite the rationalized Christian roots of gift-giving, the practice ultimately steered Christmas closer to the secularized holiday it is today. Stores began placing Christmas-themed ads in newspapers in 1820. Santa Claus, the increasingly popular bearer of gifts, started popping up in ads and stores 20 years later. By 1867, the Macy’s department store in New York City stayed open until midnight on Christmas Eve, allowing last-minute shoppers to make their purchases.

Today, Christmas is a bonafide gift-giving bonanza. Desperate parents scrabble over the under-stocked toy of the season. Stores bring out the tinsel and greenery in early October. And sale-enthusiasts queue up before dawn the day after Thanksgiving. Most retailers rely on the holidays to make up for the summer doldrums and prepare for the slow sales of the New Year. This dependence has made Christmas, a single day in late December, swell into a three month holiday season. “The holidays” — with their sales, decorations and mall Santas — now reign through nearly a quarter of the year.

Some shoppers appreciate the early bird merchants. They make their purchases over the summer or in the early fall to avoid stress or save money. But for many consumers, October allusions to Christmas only serve as an annoyance, or, in some cases, even a deterrent from shopping at all. In response to consumer complaints, many stores have adopted subtler holiday tactics. They still begin their sales and ad campaigns in early October but hold back the overt holiday images and greetings until closer to November [source: New York Times].

Christmas Traditions

Christmas traditions have a way of feeling timeless — you may have seen the same ornaments, sung the same songs and eaten the same foods for your entire life. Some Christmas traditions are, in fact, ancient. They have pre-Christian roots and originate from pagan winter-solstice celebrations or Roman festivals. Other traditions are relatively modern — either rescued from oblivion or conjured up in the surprisingly recent past. Some significant holiday traditions include decorations, activities and food.

Christmas Decorations

With Americans spending about $8 billion annually on Christmas decorations, it’s clear that tinsel, green trimmings and electric lights are an important part of most peoples’ holiday. Evergreen trees and garlands were used as decorative symbols of eternal life by ancient Egyptians, Chinese and Hebrews; European pagans sometimes worshiped evergreen trees. By medieval times, western Germans used fir trees to represent the Tree of Paradise in mystery plays about Adam and Eve. They decorated the trees with apples and later with wafers to symbolize the host. The trees grew increasingly popular in Germany and settlers introduced them to North America in the 17th century. Many people also decorate with holly, mistletoe and ivy. Decorators started lighting up their trees with electric bulbs in the 1890s. Since then, lights have become an integral part of Christmas decorating.

Christmas Activities

Outdoor light displays and other decorating traditions have created Christmas activities of their own. Decorators sometimes compete over the most ornate lighting displays and spectators walk or drive through neighborhoods to marvel at the exhibits. Schools and churches often stage Christmas pageants that reenact the nativity scenes. Saint Francis of Assisi started this custom in 1223, believing a life-size staging of the crèche would make Jesus’ story clear and accessible. Christmas pageants might also include traditional carols that are still sometimes sung door to door by groups of friends or neighbors.

Christmas Food

Traditional Christmas food often gets a bad rap — there’s green beans soaked in mushroom soup, potentially primordial fruitcake and blob-like figgy pudding that, for some reason, made carolers sing “we won’t leave until we get some.” But Christmas fare is also a delicious combination of harvest feast foods, like turkey, squashes and potatoes; winter festival foods like roasted meats and an array of baked goods that outdoes any other time of year. Many novelty treats mimic other Christmas traditions: the Bûche de Nöel imitates the Yule log, gingerbread houses copy well-trimmed colorful chalets and cookie cutters turn out legions of trees, stars and Santas.

Was Jesus Really Born Dec. 25?

At Christmastime, you might notice signs amid residential light displays or on church boards that merrily proclaim “Happy Birthday, Jesus” or announce that “Jesus is the reason for the season.” Of course, such messages are merely meant to remind people of the sentiment behind Christmas for Christians. But the signs do raise questions about the accuracy of Biblical dates and the history of the Church year.

But by the early fourth century, Church leaders decided they needed a Christian alternative to rival popular solstice celebrations. They chose Dec. 25 as the date of Christ’s birth and held the first recorded Feast of the Nativity in Rome in A.D. 336. Whether they did so intentionally or not, Church leaders directly challenged a fellow up-start religion by placing the nativity on Dec. 25. The Cult of Mithras celebrated the birth of their infant god of light on the very same day.

Church leaders may have also had theological reasons for choosing Dec. 25. The Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus had identified the 25th as Christ’s nativity more than 100 years earlier. Chronographers reckoned that the world was created on the spring equinox and four days later, on March 25, light was created. Since the existence of Jesus signaled a beginning of a new era, or new creation, the Biblical chronographers assumed Jesus’ conception would have also fallen on March 25 placing his birth in December, nine months later.

Lots More Information

How Do They Determine What Date Easter Will Occur On?

By: Kathryn Whitbourne | Updated: Feb 3, 2021

According to the English Book of Common Prayer, “Easter Day is the first Sunday after the full moon which happens upon, or next after the 21st day of March; and if the full moon happens upon a Sunday, Easter Day is the Sunday after.”

Why such an odd definition? March 21 is the usual date of the spring or vernal equinox — the day on which the length of daylight equals the length of darkness as the days are lengthening in the spring. Sometimes the equinox falls on March 19, 20 or 22. But for simplicity’s sake, most church leaders use March 21 as the start for determining the date of Easter. Using this method, Easter can only occur between March 22 and April 25.

The traditional Jewish calendar is based on moon phases, which is how the phase of the moon enters into the definition. Passover begins on the 15th of Nissan, based on the Jewish calendar, typically on the night of the first full moon after the vernal equinox. This could either be in March or April. That’s why Passover and Easter celebration days often overlap or are close together. When Christians were determining what day Easter would fall on, they deferred to the Jewish practice of using moon phases to decide the timing of holidays.

Counting 40 days backward from Easter Sunday (not including any other Sundays) will give you the date for Ash Wednesday.

When Did Jesus Die? Scholars Are Divided

By: Dave Roos | Apr 5, 2023

Biblical math is tricky stuff, and centuries of Bible scholars (and even some scientists) have scoured the New Testament trying to calculate the exact date when Jesus died. The leading contenders are April 7, 30 C.E. or April 3, 33 C.E. Why two different dates? You’ll see in a minute.

For expert assistance, we recruited Helen Bond, religion professor at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and co-host (with this author) of a podcast called Biblical Time Machine.

Contents

- Biblical Clues to the Date of Jesus’ Death

- Was Jesus Killed on Passover or the Day Before?

- Or Was It Another Date?

Biblical Clues to the Date of Jesus’ Death

The Jewish calendar at the time was lunar, meaning that the first date of each month was determined by when the light of a new crescent moon was visible in the holy city of Jerusalem. The setting sun meant the end of one day and the new moon meant the beginning of the next. Daylight hours were measured from sunrise, so the first hour was 6 a.m., the third hour was 9 a.m., the sixth hour was noon, and the ninth hour was 3 p.m. Some of these times were included in the biblical accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion. For instance, Luke 23:44-46 says:

“It was now about the sixth hour [noon], and darkness came over the entire land until the ninth hour [3 p.m.], because the sun stopped shining; and the veil of the temple was torn in two. Jesus called out with a loud voice, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” When he had said this, he breathed his last.”

All four of the gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) agree on a basic chronology of events ending with Jesus’ crucifixion on a Friday:

● Thursday evening: Jesus Christ shared a meal (known as “the Last Supper“) with his disciples and was arrested later that night.

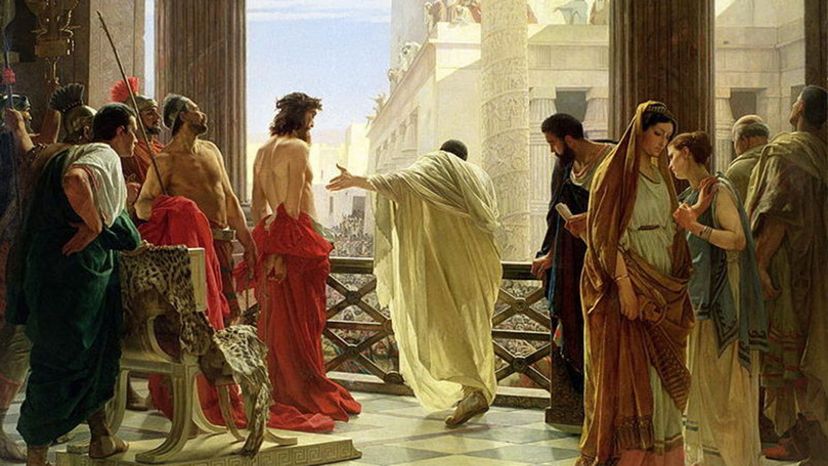

● Friday morning: Jesus was tried by Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect, and executed Friday afternoon.

● Friday evening: Jesus was hastily buried in the tomb right before sunset on Friday, the beginning of Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath.

We can be fairly sure that the date we’re looking for has to land on a Friday. So far, so good.

What about the year? The Bible does not give us a lot of specific dates, but it does reference specific historical figures. By cross-referencing those names with dates provided by outside sources (mostly the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus), we can be fairly certain that the death of Jesus happened sometime within these time frames:

● The reign of Tiberius Caesar, the Roman emperor: 14 C.E. to 37 C.E.

● When Pontius Pilate was prefect in Judaea: 26 C.E. to 36 C.E.

● When Caiaphas was high priest in Jerusalem: 18 C.E. to 36 C.E.

However, there are still some other timeline issues to try and resolve.

Was Jesus Killed on Passover or the Day Before?

Here’s where we run into our first disagreement. All four gospel accounts agree that Jesus was killed on a Friday sometime during the Passover holiday, but was it on Passover itself or was it the day before?

● In the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke (known collectively as the “synoptic” gospels), Passover falls on a Friday, so Jesus was tried and killed on the very day of Passover.

● In the gospel of John, however, Passover falls on a Saturday, so Jesus was tried and killed the day before Passover, known as the Day of Preparation. (A Passover feast would have had to be prepared the day before the Sabbath, because of the biblical injunction to do no work on the Sabbath.)

Why is it so important whether Passover landed on a Friday or a Saturday? Because that will determine in which years the crucifixion could have happened. Thanks to computers, we can search for dates between 26 and 36 C.E. (when the date ranges above overlap) and when Passover either landed on a Friday or a Saturday.

Using those criteria, you get three possible dates for the crucifixion (depending on the gospel):

● April 11, 27 C.E. (Mark, Matthew, Luke) on Passover

● April 7, 30 C.E. (John), the day before Passover

● April 3, 33 C.E. (John), the day before Passover

Most scholars think that 27 C.E. is too early, since the gospel of Matthew indicates that John the Baptist began preaching in the “fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius,” which would have been 28 C.E. at the earliest. In the Bible’s chronology, Jesus begins his mission after John, so 28 C.E. is the absolute earliest starting date.

And that’s how biblical scholars ended up with two finalists for the date of Jesus’ crucifixion: April 7, 30 and April 3, 33.

Bond writes that the majority of scholars side with April 7, 30, as the true date. This is the date favored by people who believe that Jesus’ mission was relatively short or that it began as early as 28 C.E. A smaller group of scholars are just as certain about April 3, 33, believing that Jesus’ mission lasted three years and started closer to 30 C.E. They also affirm this date because it coincided with a lunar eclipse, which Pilate may have referenced in a letter to the emperor Tiberius.

Or Was It Another Date?

Faced with contradicting gospels and four possible dates for the crucifixion, Bond has her own theory: They’re all wrong. Or to put it another way, the gospel writers were less concerned with historical accuracy than with writing a spiritually and theologically compelling narrative.

In John’s gospel (specifically John 19:14), Jesus is crucified at noon on the Day of Preparation for the Passover, the exact time when the paschal lambs were being slaughtered for the ritual Passover meal or seder.

“John chose to time the crucifixion with the Day of Preparation for theological reasons,” says Bond. “The whole point for John is that Jesus is the new Passover lamb. He’s going to die on the cross as the new Passover sacrifice.”

Mark’s gospel, too, had its own theological motivations for choosing Passover itself as the day that the Romans crucified Jesus.

“According to Mark, the Last Supper takes place at exactly the same time as the other Jews are celebrating the Passover seder,” says Bond. “Mark wants to say that the Last Supper, with its institution of the Lord’s Supper (the bread and wine), is a sort of replacement for the Passover meal.”

Bond thinks that it’s far more likely that Jesus was arrested and killed several days or even a week before Passover. It makes sense that both the Jewish authorities and Pilate would have wanted to be rid of this “troublemaker” before the holiday began. But if Jesus’ followers knew that he was crucified “around Passover” or “at Passover time,” the juxtaposition of Jesus’ death and Passover would have grown increasingly significant.

By the time the gospels were written, decades after the events they describe, “Passover would have had this magnetic pull, so that everything ends up happening ‘on the Passover’ instead of ‘around the time of Passover,'” says Bond. “Both of the dates in John and Mark are probably wrong historically, but they represent important early reflections on the meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection.”

Who Was Pontius Pilate, Before and After Jesus’ Crucifixion?

By: Dave Roos | Apr 11, 2022

At its peak, the Roman Empire included 40 provinces covering much of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, yet historians know very little about the men put in charge of governing these Roman outposts. Pontius Pilate is one of the exceptions.

Pilate presided for 10 years as the governor or “prefect” of Judea, from 26 to 36 C.E., and his name is immortalized in the New Testament as the man who oversaw the trial and crucifixion of Jesus. Yet the Bible isn’t the only ancient source of information about Pilate. Historians like Josephus and Philo of Alexandria fill in a portrait of Pilate as an unprepared and hotheaded ruler of a problematic province.

“You have the impression that Pilate doesn’t understand the complexities of the province and the sensitivities of the people he was governing,” says Helen Bond, professor of Christian origins at The University of Edinburgh and author of “Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation.” “On the other hand, they weren’t making it very easy for him. It was a bit of a minefield.”

Contents

- Where Did Pilate Come From?

- Pilate the Pawn

- Pilate the Saint

- Pilate the Harsh Ruler

- Where Did Pilate Go After Judea?

Where Did Pilate Come From?

We don’t know much about Pilate’s life before his posting in Judea, but some things can be inferred from his title “prefect” or praefectus in Latin, which means “one who stands in front.”

“Praefectus is a military title,” says Bond. “Judea had only been under direct Roman rule for 20 years when Pilate arrived, so it was still a military posting. The whole point is to repress the natives and keep law and order.”

Prefects like Pilate came from second-tier noble families, says Bond, and were chosen because of their ability on the battlefield. Pilate’s family names Pontius and Pilatus may have referred to the region the family originally hailed from — possibly the Kingdom of Pontus on the southern coast of the Black Sea — or some connection with javelin throwers, because pilatus means “spear.” Pilate would have had a first name, too, like Marcus or Gaius, but that’s been lost to history.

Bond says that as a military man, Pilate would have had limited experience and training in diplomacy or governance, something Roman authorities may not have deemed necessary for an unimportant outpost like Judea.

“Pilate was in Judea seeing to national security and he left the day-to-day administration to the chief priests in Jerusalem,” says Bond. “Mostly he was just making sure there were no riots.”

Pilate the Pawn

The trial of Jesus is recounted with slight variations in all four New Testament gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The gospels paint a clear picture of Pilate as a weak governor being bullied by the Jewish authorities into condemning an innocent man to a slow and agonizing death.

“I find nothing wrong with this man!” Pilate tells the angry crowd in Luke. And in John, Pilate is desperate not to get involved, and tells Caiaphas, the chief priest of the Jewish Temple, to “take [Jesus] away and judge him by your own law.”

When the Jewish leaders refuse, telling Pilate they don’t have the authority to execute Jesus, Pilate tells the crowd that they can release one of two prisoners, the innocent Jesus or Barabbas, a murderer. They roar “Barabbas!” and insist that Pilate crucify Jesus for claiming to be “King of the Jews.” Literally “washing his hands” of guilt, Pilate orders the execution.

“The Bible’s portrayal of Pilate is not a very positive picture of a Roman governor,” says Bond. “I think a first-century audience would have been quite shocked.”

Even if Pilate was afraid of a riot and wanted to “pacify the crowd,” as it says in Mark, it was fully within his authority as governor to refuse the trumped-up charges against Jesus. The truth is that historians have no idea what actually happened at Jesus’ trial (if there was one) and must rely on the gospel accounts, which have their own biases.

“The main thing that the gospel writers wanted to show was that Jesus is innocent,” says Bond, “and that his crucifixion was a mixture of Jewish pressure and a pretty hopeless governor who wanted to get rid of the case.”

Pilate the Saint

The books of the New Testament aren’t the last word on Pilate. There are a number of early Christian writings that didn’t make it into the Bible (called the “Apocrypha”) but were in wide circulation in the first centuries of Christianity. Some present an increasingly positive view of Pilate and a few even cast him as a true believer.

“The Gospel of Nicodemus,” likely written in the fourth century C.E., is presented as an eyewitness account of the trial of Jesus by Nicodemus, a pharisee who is sympathetic to Jesus and his followers. The text describes Roman standard-bearers bowing to Jesus as he is led into the trial, and Pilate raging against the Jewish authorities for forcing his hand to crucify “a just man.”

Later texts known as “The Letters of Herod and Pilate” purport to be actual correspondence between Pilate and Herod Antipas, the king of Galilee, about the trial of Jesus. In Pilate’s letter, he and his wife are visited by the resurrected Jesus, whom they recognize as the Son of God and beg forgiveness for their sins.

Bond says that while these texts are “a million miles away from anything that may be historical,” they recast Pilate as a repentant sinner who ultimately accepted Jesus as his Savior. In some Christian traditions, including the Ethiopian Church, Pilate and his wife Procla even achieved sainthood.

Pilate the Harsh Ruler

Philo of Alexandria was a Jewish-Roman historian who lived in Egypt at the same time that Pilate was governor of Syria. His writings are the closest thing we have to a contemporary historical account of Pilate’s tenure in Judea — even the gospels were written decades later — but Philo had his own problems with Pilate.

“Philo really hates Pilate,” says Bond. “He doesn’t have a good word to say. He says Pilate was vain, savage and stubborn, and that he put people to death without trial.”

Philo’s main beef with Pilate was that he brought gilded shields called “standards” into Jerusalem, which insulted the Jewish authorities and Temple priests. When the Jewish leaders protested, Pilate refused to remove the statues. According to Philo, it took a sharply worded letter from Emperor Tiberius himself to convince Pilate to take down the standards.

Josephus was another Jewish-Roman historian who was born soon after Pilate’s stint in Judea. Josephus is famous for being the only nonbiblical ancient source to mention Jesus, although his brief account was “clearly worked over by Christian editors,” says Bond, and must be taken with a grain of salt.

As for Pilate, Josephus tells us of another blow-up with the Jewish authorities, when Pilate tried again to have some busts of the emperor displayed in Jerusalem. When a crowd of Jewish protesters gathered outside of Pilate’s headquarters in the coastal town of Caesarea, Pilate ordered his soldiers to surround them. According to Josephus, the Jews “astonished” Pilate with their willingness to die rather than endure the insult, so Pilate relented and removed the statues. In another incident, he had an aqueduct constructed with sacred funds from the treasury of the Jewish temple. When people protested, Pilate had soldiers go among the crowd disguised as civilians with clubs under their coats which they used to beat the protesters, many to death.

Where Did Pilate Go After Judea?

The last news we hear about Pilate also came from the pen of Josephus and involved another controversy over a man claiming to be the Messiah.

In 36 C.E., a Samaritan man declared that he was a reincarnation of Moses and led a group of followers on a trek up Mount Gerizim, where he prophesied that great wonders would be revealed to them, including sacred vessels buried there by Moses. Word got to Pilate that these men were planning an armed uprising.

“They all start to go up the mountain but Pilate decides the best thing is to nip this in the bud,” says Bond. “So, he sends in the cavalry, they kill loads of people, execute the leaders and that’s the end of the uprising.”

The Samaritans complained about Pilate’s violence to the legate of Syria, a higher-ranking Roman governor, who ordered Pilate to return to Rome and make his case directly to Tiberius, the emperor. But before Pilate reached Rome, Josephus says, Tiberius died and was replaced by Caligula. It’s unknown whether Pilate’s hearing went badly and he was removed from his post, or else he simply decided to retire.

“Pilate had been in Judea for 10 years at that point, so it was probably a good time to have a change,” says Bond. “Once he goes back to Rome, we know absolutely nothing more about what happens to him, apart from the non-canonical stories and legends we hear about him.”

In one of those legends, Pilate was banished from Rome and ended up dying (committing suicide?) in Vienna, Austria, where he was believed to emerge every Easter from a local lake clad in purple robes, and anyone who looked at him would die within the year. A related legend placed his final resting place on Mount Pilatus near Lucerne, Switzerland, where his evil spirit is said to be responsible for bouts of nasty weather.

How Old Was Jesus When He Died?

By: Dave Roos | Mar 2, 2023

During the Easter season, Christians celebrate Jesus’ resurrection from the dead, just days after his crucifixion at the hands of the Romans. Whether you’re religious, agnostic or atheist, it’s hard to ignore the influence of Jesus Christ and the Bible in Western culture. But how much can we really know about the historical Jesus’ timeline from Biblical accounts? Do we even know how old Jesus was when he died?

Helen Bond is a religion professor at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the co-host (with this author) of a podcast called Biblical Time Machine. She says that the Bible is surprisingly skimpy when it comes to basic details about Jesus — what he looked like, whether he was married, etc. — and is frustratingly vague or contradictory when establishing facts like when Jesus was born and when exactly he died.

“We don’t know the dates of anything with any specificity,” says Bond, who nonetheless tried to decipher the exact date of the original Easter in an excellent article titled “Dating the Death of Jesus.”

Many people who follow the Christian faith believe that Jesus was 30 when he was baptized, and that his earthly mission lasted exactly three years, citing certain biblical passages. This would mean Jesus died at the age of 33. But a closer look at the Bible reveals some fuzzier math.

Wasn’t Jesus 30 When He Started His Ministry?

In the New Testament, there are four separate biographies of Jesus known as the four gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Biblical scholars believe that the gospel of Mark was written first, and that the authors of Matthew and Luke elaborated upon Mark’s account. The gospel of John was written last and includes some stories that are not in the earlier texts. Only one of the four gospels directly addresses Jesus’ age.

“Mark, the earliest gospel, says nothing at all about Jesus’ age,” says Bond. “When Luke rewrites Mark’s story, he says that ‘Jesus himself was about thirty years old when he began his ministry.’ Maybe that comes from specific knowledge, maybe it comes from eyewitnesses, or maybe it’s his general take on Mark, but that’s the only place where we have any kind of age for Jesus.”

That verse in Luke 3:23 is the basis for the widespread belief that at age 30 Jesus began publicly teaching and performing miracles. But the text only says that Jesus was “about thirty,” which could mean that he was 29, 31 or even a youthful-looking 40.

The only other clue about Jesus’ age comes in the gospel of John (John 8:57-59), when Jesus tells a group of Jewish leaders that he knew Abraham, the Old Testament patriarch. “You aren’t even 50 years old!” the Jewish leaders reply. “How can you say that you have seen Abraham?”

Taken together, the two verses in Luke and John paint a picture of a youthful Jesus in the prime of his life, but the gospels are not precise about his age. Today we might find this strange, but it wouldn’t have fazed people in the first century C.E.

“This was a society where people didn’t know with any degree of precision when they themselves were born,” says Bond. “It’s a modern thing for us to be able to say exactly when things happened.”

Didn’t Jesus Teach for Three Years?

This is another Bible “fact” that isn’t as cut-and-dried as you might think.

Nowhere in the New Testament does it explicitly say that Jesus’ ministry — from his baptism by John until his crucifixion in Jerusalem — lasted three years. The way that number has been calculated is by counting how many times the Bible says that Jesus traveled to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover, the annual Jewish holiday commemorating the Exodus from Egypt.

In Mark, the earliest gospel, there’s only one mention of a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, during which Jesus is arrested, tried and sentenced to death. By that calculation, some scholars think that Jesus’ ministry was just one year or less.

But in the gospel of John, Jesus appears to make three separate pilgrimages to Jerusalem to observe Passover — John 2:13, John 6:4 and John 12:1 — and is killed during the third trip. That’s where we get the idea that his ministry was three years long.

In fact, some experts place Jesus’ death age at about 37 bearing in mind that he was born during King Herod’s reign around 4 or 5 B.C.E., and that John the Baptist started preaching in the 15th year of Roman emperor Tiberius’ reign (according to Luke 3:1), which would be 29 C.E. This is also when Jesus began his earthly ministry. Adding in three years for the three Passovers and these scholars determine that Jesus was 36 or 37 years old when he died.

But Bond says that John’s repetition of the Jerusalem pilgrimage might reflect the author’s theological interests more than any historical reality.

“The author of John is very keen on Jesus coming down to Jerusalem and being the replacement for Jewish feasts,” says Bond, “so you have to ask, are there theological reasons for this or did Jesus’ ministry really last that long?”

Another strike against the “three-year” theory is that the gospel of John, while important theologically, is “not generally noted for its historical accuracy,” Bond says. John was the last of the gospel narratives of Jesus’ life to be written, likely between 80 and 100 C.E., putting at least half a century between the author and the events he described.

Where does that leave us? Since it’s unclear if Jesus’ ministry was one year or three years long, and it’s also unclear if Jesus was 30 or “about 30” when he began his ministry, it’s very difficult to calculate with any certainty exactly how old Jesus was when he was crucified.

10 Myths About Christmas

By: Melanie Radzicki McManus | Updated: Dec 3, 2021

One of the most beloved Christmas traditions, especially in America, is decorating a Christmas tree. Most people think it’s been around, well, forever. But the Christmas tree is actually a pretty recent holiday tradition.

German immigrants brought the tradition to the United States in the mid-18th century, yet 100 years later it still hadn’t really caught on. In fact, it was downright controversial. The New York Times wrote an editorial against the practice in the 1880s, and when Teddy Roosevelt was president in the early 1900s, he railed against cutting down trees for Christmas, saying it was a waste of good timber [source: Shenkman]. The tradition, of course, took hold regardless.

Despite Christmas’ popularity among Christians and non-Christians alike, little-known facts like this — and even outright myths — abound. From the holiday’s religious origins to Mr. and Mrs. Claus to that great, evergreen symbol, the Yuletide tree, here are 10 enduring Christmas myths, exposed at last.

Contents

- Christmas Is the Most Important Christian Holiday

- Clement C. Moore Wrote “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”

- Jesus Was Born on Dec. 25

- Germans Always Put Pickle Ornaments on Their Trees

- Abbreviating Christmas as “Xmas” Is Sacrilegious

- Santa Claus, St. Nicholas and Father Christmas Are All the Same

- Three Kings Visited Jesus Shortly After His Birth

- Boxing Day Is for Boxing Up Gifts for Return

- U.S. Students Can’t Sing Religious Carols in Public Schools

- “Jingle Bells” Is a Christmas Song

10: Christmas Is the Most Important Christian Holiday

Say it ain’t so! Yes, to the astonishment of many people — including many Christians — Christmas is not the most important Christian holiday. Despite the ribbons. Despite the tags. Despite the packages, boxes and bags. No, Christmas can’t hold a candle to that powerhouse Christian holiday, Easter. And it’s not just an Easter bunny versus Santa Claus thing, either.

On Christmas, Christians celebrate the birth of Jesus, who they believe is the son of God. That’s definitely an important event, and Christians whoop it up in celebration. But Easter commemorates Jesus’ rising from death into eternal life, which was not only a coup for Jesus personally, but for all of humankind, as his resurrection is said to have contained the promise of eternal life for all who believe in him [source: Martin].

Because Easter is so sacred, Christians spend nearly two months of the year celebrating the Easter season, far longer than they celebrate Christmas. Think of it this way: Everyone has a birthday, but not everyone can triumph over death.

9: Clement C. Moore Wrote “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”

How many of us snuggle with family members every Christmas season to read “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” aka “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”? This poem has been popular since it was first published in New York’s Troy Sentinel on Dec. 23, 1823 [source: Conradt].

The poem was published anonymously, and it wasn’t until 1836 that someone stepped forward as the author: Clement Clarke Moore, a professor and poet. According to Moore, he wrote the poem for his kids, and later, unbeknownst to him, his housekeeper sent it to the newspaper. But once Moore claimed to be the author, members of the Henry Livingston Jr. family cried foul, saying their dad had been reciting the very same poem to them a full 15 years before it was published. Livingston, interestingly, was a distant relative of Moore’s wife [sources: Conradt, Why Christmas].

Who was telling the truth? At least four of Livingston’s kids, and one neighbor, said they remembered him reciting the poem as early as 1807. He was also part Dutch, and many references in the poem are, too. Plus scholars who studied Moore’s other written works say they’re all vastly different in structure and content from “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” But Moore did claim authorship first. He was also friends with Washington Irving, who knew all about Dutch culture and had previously written about St. Nicholas [sources: Howse, Conradt]. Add all these clues together and the question of the famous poem’s authorship is still up in the air.

8: Jesus Was Born on Dec. 25

If Christmas is the celebration of Jesus’ birth, and Christmas is always on Dec. 25, then Jesus was born on Dec. 25, right? Nope. No one knows for sure when Jesus was born. The Bible mentions neither a month nor a date. Yet while Jesus may have been born on Dec. 25, it’s highly unlikely, at least according to Biblical interpretations [source: Christian Answers]. Here’s why.

First, the Bible mentions that during Jesus’ birth, shepherds were in their fields. But it’s cold in Bethlehem in December, and nothing much grows in the fields, so shepherds sheltered their sheep around that time of year and stayed inside. The Bible also says Mary and Joseph were traveling to take part in a census. But back in Jesus’ time, censuses were normally held in September or October — after the fall harvest, yet before the harsh winter made travel difficult [source: Christian Answers].

Finally, while Easter was celebrated by the earliest Christians, Jesus’ birth wasn’t considered a special day until about the fourth century, when the church wanted some kind of celebration to take the focus away from the winter solstice celebrations favored by the pagans. Voilà — the church proclaimed Jesus’ birth date as Dec. 25, and it became a major Christian celebration. Most scholars, incidentally, agree Jesus was likely born near the end of September, based on a host of additional Biblical clues.

7: Germans Always Put Pickle Ornaments on Their Trees

You might have noticed that most ornament stores carry glass pickles. Ever wonder why? The popular story is that the pickles are part of a very old German tradition that went like this: On Christmas Eve in Germany, parents hid glass pickle ornaments deep within the fragrant branches of their trees, once all of the other ornaments were in place. The next morning, the first child to find the pickle ornament got an extra gift from St. Nicholas, while the first adult to find it (not counting the ones who hid it) would have good luck for the next year [source: German Pulse]. Not too shabby!

Unfortunately, this cute tale is a myth. Most Germans say they’ve never heard of this practice, and it’s definitely not a tradition. That’s pretty good intel. But the tale has more flaws. In Germany, as in many European countries, St. Nick traditionally delivers his gifts on the night of Dec. 5, not on Christmas Eve. Christmas Eve is also the day German kids normally open their presents, not Christmas Day. So how did this story become so well-entrenched? It’s still a mystery. Glass ornaments were being produced in Germany in the 16th century, and by the 19th century some Germans were crafting fruit- and nut-shaped ornaments. But that’s about as close as we can get to figuring it out [source: German Pulse].

6: Abbreviating Christmas as “Xmas” Is Sacrilegious

Don’t take “Christ” out of Christmas! That’s the rallying cry of many Christians, who become quite frantic over what they view as sacrilege — removing Christ’s holy name from the important holiday, and replacing it with a simple X. A secular X. An impersonal, present-and-Santa-seeking X.

But if we take a closer look, writing “Xmas” isn’t a necessarily a slam against the son of God. Far from it. The word “Christ” in Greek is written “Χριστός.” Notice anything familiar? The first letter is “X,” or chi. Chi is also written as an X in the Roman alphabet. Rather than being an offensive abbreviation for Christmas, “Xmas” is actually a quite logical nickname [sources: Boyett, Bible Suite].

5: Santa Claus, St. Nicholas and Father Christmas Are All the Same

This is a tricky one. The three are definitely different, yet sometimes can be considered the same. St. Nicholas was a fourth-century Turkish bishop who spent his life giving money to the poor, and it’s said one of his favored methods was secretly leaving money in people’s stockings overnight. Nicholas died on Dec. 6, and was eventually proclaimed a saint. Thus, Dec. 6 became known as St. Nicholas Day. Various cultures celebrated by instructing their kids to leave out stockings or shoes the night before so “St. Nick” could fill them with gifts like fruit, nuts and candy. [source: Why Christmas].

By the 16th century, Europeans were turning away from the idea of St. Nicholas, yet they loved the gifting tradition. So St. Nick morphed into a guy named “Father Christmas.” First mentioned in 15th-century writings, he was a partying dude associated with drunkenness and holiday merrymaking. In the U.S., St. Nick became Kris Kringle. Father Christmas and Kris Kringle generally brought gifts on Christmas, not Dec. 6. When Dutch settlers began emigrating to the U.S., they brought with them stories of St. Nicholas, whom they called Sinterklaas. Soon Sinterklaas became Americanized as Santa Claus [source: Why Christmas].

By the 20th century or so, all of the Father Christmases, Kris Kringles, etc., became “Santa Claus,” uniformly depicted as a round-bellied, white-bearded old guy who brings gifts on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. Yet some people around the world, namely Christians from European countries where St. Nick was a beloved hero, still celebrate St. Nicholas Day on Dec. 6 by setting out shoes or hanging stockings the night before. So while Father Christmas and Santa Claus are definitely now one and the same, St. Nicholas is still a toss-up, with some people recognizing him as a distinct individual and others lumping him in with the other gift-bearing men [source: Why Christmas].

4: Three Kings Visited Jesus Shortly After His Birth

Gaspar (or Caspar), Melchior and Balthasar, three kings from the east, are said to have traveled a long way to see Baby Jesus, following a freakishly large, bright star and hauling gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh along with them. Alas, according to the Bible this is yet another Christmas miss, despite the presence of a trio of king figurines in all nativity sets.

The Bible says magi came from the east, following a big star, and that they were looking for the King of the Jews. But magi are wise men, not kings. And the number of and names of the magi are never detailed anywhere in writing. Further, the Bible says the men arrived when Jesus was a young child, not an infant, and they found him at home with his mom — not in a manger in a stable.

Scholars believe the men were likely astrologers who arrived a year or more after Jesus’ birth. Because three gifts are listed in the Bible, scholars also say it’s possible that over time, people assumed this meant there were three men [source: Boyett]. The myth of their names emerged later, after a mosaic depicting the magi was created in the sixth century. The mosaic, housed in the Basilica di Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, contains the names Gaspar, Melchior and Balthasar.

3: Boxing Day Is for Boxing Up Gifts for Return

Lots of people have never heard of Boxing Day. Those who have — and who know it falls after Christmas — often think it’s a day designated for boxing up any gifts you don’t want, don’t like or can’t use, and taking them back to the store. Nice as that may sound to anyone who’s used to receiving bum gifts, unfortunately it’s completely wrong.

Boxing Day is Dec. 26, and it’s a celebration that takes place only in a few countries. It started in the United Kingdom during the Middle Ages as the one day of the year when churches opened their alms boxes, or collection boxes, and doled out the money to the poor. Servants were also given this day off to celebrate Christmas with their families, having had to work for their bosses on Christmas Day [source: Why Christmas].

The holiday changed over time. In the years leading up to World War II, blue collar workers such as milkmen, butchers and newspaper boys used the day to run their routes and collect Christmas tips from clients. Today, in certain countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, Boxing Day is a day when certain sporting events are held, namely horse races and soccer matches [source: Why Christmas]. What that has to do with alms for the poor — or boxes — is another mystery.

2: U.S. Students Can’t Sing Religious Carols in Public Schools

This idea is false — at least for now. As long as secular songs are included in a school holiday concert’s repertoire, Christmas carols may also be sung [source: Gibbs, Jr. and Gibbs III]. But there’s much debate over whether singing any sacred choral music in public schools is a violation of the U.S. Constitution‘s Establishment Clause. The Constitution’s First Amendment says “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” This “Establishment Clause” is at the heart of many disputes over what people consider freedom of conscience, freedom of speech and freedom of religion [source: Kasparian]. As of now, however, there’s been no ruling by the Supreme Court, and no Constitutional amendments, banning this practice. Some individual school districts, however, have banned Christmas music in school concerts [source: Rundquist].

1: “Jingle Bells” Is a Christmas Song

“Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way” — one of the best-known Christmas songs ever written. Right? Well, not exactly. We know it as a Christmas classic, but it wasn’t written that way. It was actually written as a Thanksgiving song. Yes! We know! Jingle Bells! What? Originally titled “One Horse Open Sleigh,” the song was written by American composer James Lord Pierpont in the 1850s and was about the annual sleigh races held around Thanksgiving in the town of Medford, Massachusetts.

Lots More Information

Author’s Note: 10 Myths About Christmas

Thank goodness my frequent use of the term “Xmas” isn’t offensive. Now I’m going to go hang my pickle ornament on the tree, read whoever’s “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” and call it a day.

Related Articles

- 10 Historical Untruths About the First Thanksgiving

- How Christmas Works

- How Mistletoe Works

- Is Black Friday the biggest shopping day of the year?

- Could holiday foods help save the planet?