Reading the New Testament with Historical Clarity

Reader’s Note:

This study is offered in a spirit of care and concern for the body of Christ; biblically defined as the “assembly”. Its purpose is not to disparage any people or to advance political agendas, but to encourage careful, biblical discernment. The conclusions presented are grounded in Scripture and historical sources, and readers are encouraged to examine them prayerfully and in light of the whole counsel of God.

Preface: Understanding Israel, Judah, and the People Called “Jews”

It is strongly believed if the average evangelical Christian understood the historical and biblical realities surrounding Israel, Judah, and the people later called “Jews,” they would read both the Old and New Testaments with greater clarity and discernment. Passages in books such as Obadiah and Ezekiel would no longer seem distant or obscure, but would instead illuminate the religious and historical backdrop of the New Testament. These prophetic writings reveal long-standing patterns of covenant failure, misplaced identity, and spiritual presumption—patterns that did not disappear with the close of the Old Testament, but continued into the time of Christ.

When read in this light, the conflicts recorded in the Gospels are no longer puzzling or abrupt. Jesus’ confrontations with the Jerusalem leadership emerge as the culmination of issues already addressed by the prophets. Likewise, the apostles wrote within this same historical framework, consistently redefining identity not by lineage, location, or religious status, but by faith, repentance, and fruit.

What is often overlooked is how modern assumptions about Jewish and Israeli identity influence Christian theology and biblical interpretation. Many believers unintentionally project contemporary definitions backward onto Scripture, assuming continuity where the biblical record emphasizes disruption, judgment, and the need for restoration. Scripture presents a sobering truth: God judged His covenant people not despite their identity, but because they bore His name while failing to walk in His ways.

The period following the Babylonian captivity reinforces this lesson. Though God mercifully allowed a remnant to return to Jerusalem, the problems that led to judgment were not automatically resolved. Over time, religious authority became increasingly entangled with political power, and tradition often replaced obedience. This environment formed the backdrop against which Jesus spoke with such clarity and urgency.

So, the purpose in raising these matters is not to provoke controversy, but to encourage discernment. Scripture consistently measures identity by obedience and fruit, not by ancestry, geography, or profession. If Christians fail to learn from this history, it risks repeating the very errors Scripture warns against.

It’s hoped that this study will encourage believers to read the whole counsel of God—prophets and apostles alike—within their proper historical and biblical context, so that truth may be discerned clearly and faithfulness preserved.

Introduction: Why Definitions Matter

One of the most persistent sources of confusion in modern Christian theology is the uncritical reading of ancient terms through contemporary assumptions. Few words illustrate this problem more clearly than the word “Jew” in the New Testament. For many readers, the term automatically implies a direct, uninterrupted ethnic lineage from the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to the modern Jewish people. Yet Scripture itself never invites such an assumption.

When modern meanings are imposed upon ancient words, entire theological systems can be distorted. The New Testament was written within a specific historical, linguistic, and political context. Ignoring that context has led many Christians to misunderstand who Jesus confronted, who opposed Him, and how identity is defined in the gospel. This article seeks to restore clarity by examining the term Ioudaios—translated as “Jew”—and demonstrating that it is primarily a geographical and political designation, not a guaranteed marker of covenant lineage or spiritual standing. Jesus’ own standard for discernment remains decisive:

“Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them” (Matthew 7:20).

This principle governs the entire discussion.

I. The Meaning of “Jew” in Scripture: A Geographic Term

The Greek term Ioudaios corresponds to the Hebrew Yehudi, meaning a person associated with Judah or the region of Judea. Its earliest biblical usage reflects this limited scope.

The first appearances of the term occur in:

- 2 Kings 16:6

- 2 Kings 25:25

In both cases, Yehudi refers to individuals connected to the southern kingdom of Judah, not to all Israelites, and certainly not to a universal ethnic or religious category.

By the Second Temple period, Ioudaios had become a regional identifier, similar to how one might say “Galilean” or “Syrian.” It denoted residency, political allegiance, and cultural association with Judea—not covenant faithfulness or ancestral purity.

This distinction is crucial, because Judea in the first century was not ethnically homogeneous. See Appendix “A” for details on ethnically heterogeneous rather than

homogeneous.

II. Judea’s Mixed Population: The Idumean Conversion

Following the Babylonian exile, Judea was repopulated primarily by descendants of Judah, Benjamin, and Levi—the remnant of the southern kingdom. However, a dramatic demographic change occurred in the second century BC.

Around 125 BC, the Hasmonean ruler John Hyrcanus I conquered Idumea (biblical Edom). According to the Jewish historian Josephus, Hyrcanus forcibly converted the Idumeans to Judaism:

“Hyrcanus subdued all the Idumeans; and permitted them to stay in that country, if they would circumcise their genitals, and make use of the laws of the Jews; and they were so desirous of living in the country of their forefathers, that they submitted to the use of circumcision, and of the rest of the Jewish ways of living.”

(Antiquities 13.9.1)

From that point forward, Edomites were legally “Jews”—Ioudaioi—by law and geography, not by descent from Jacob.

This fact alone explains much of the tension in the Gospels. By the time of Christ:

- The Herodian dynasty was Edomite by blood.

- The Sadducean priestly elite was closely tied to political power.

- Roman favor, not covenant faithfulness, preserved authority.

These were Judaeans1 in title—but not necessarily Israelites in lineage or faith. See here for an expanded history on the Edomites (Idumeans)

These demographic realities did not arise suddenly in the first century but were shaped by earlier post-exilic, political, and prophetic developments that must be considered before examining the Gospel accounts.

III. Intermarriage, Idumean Incorporation, and Prophetic Framing

An accurate understanding of first-century Judaean identity requires holding together three converging realities: post-exilic intermarriage, the later incorporation of Idumeans (Edomites) into Judaean society, and the prophetic witness concerning Edom’s relationship to Judah and Israel.

Post-Exilic Intermarriage among Returned Judeans

When the remnant of Judah returned from Babylonian exile, Scripture records that intermarriage with surrounding peoples quickly became a serious concern, even among leaders. Ezra describes his grief upon learning that “the people of Israel, and the priests, and the Levites, have not separated themselves from the people of the lands” (Ezra 9:1–2). The foreign peoples named—Canaanites, Ammonites, Moabites, Egyptians, and others—were outside the covenant lineage.

Nehemiah later records the same problem persisting into the next generation:

“In those days also saw I Jews that had married wives of Ashdod, of Ammon, and of Moab: And their children spake half in the speech of Ashdod, and could not speak in the Jews’ language” (Nehemiah 13:23–24).

These passages do not suggest that Israel ceased to exist as a people, nor do they provide numerical data concerning the long-term genealogical outcome. They do, however, demonstrate that ethnic purity was already under strain in post-exilic Judah, and that “Jew” (Yehudi) increasingly functioned as a community and territorial identity, rather than a guaranteed marker of unmixed descent from Jacob.2

Idumean (Edomite) Incorporation into Judaean Identity

A more dramatic and historically documented shift occurred during the Hasmonean period, roughly a century before Christ. John Hyrcanus I conquered Idumea (biblical Edom) and forcibly incorporated the Idumeans into Judaean society by compelling circumcision and observance of the Judaean law.

Josephus records:

“Hyrcanus subdued all the Idumeans; and permitted them to stay in that country, if they would circumcise their genitals, and make use of the laws of the Jews; and they were so desirous of living in the country of their forefathers, that they submitted to use of circumcision, and of the rest of the Jewish ways of living.3 4

From this point forward, Idumeans were incorporated into Judaean society through enforced circumcision and adherence to Jewish law. While Josephus does not explicitly state that they were renamed Ioudaioi, he treats those who lived according to Jewish law and custom as Jews in practice. It is within this historical context that the Herodian dynasty arose. Herod the Great, Rome’s client king over Judea, was Idumean by descent, not an Israelite, and owed his authority to Roman appointment rather than covenant lineage.³5

By the first century, therefore, the term “Jew” or “Judaean” encompassed multiple overlapping identities: descendants of Judah and Benjamin, Levitical families, post-exilic intermarried populations, and Edomite converts who had become politically and socially prominent.

Prophetic Framing: Edom and the Appropriation of Judah

Long before these historical developments unfolded, the prophets framed Edom as a persistent adversary of Judah—not merely through open hostility, but through opportunism and appropriation.

Obadiah offers the most concentrated indictment:

“In the day that thou stoodest on the other side, in the day that the strangers carried away captive his forces… even thou wast as one of them” (Obadiah 1:11–14).

Ezekiel expands this theme by recording Edom’s claim upon Judah’s inheritance:

“Because thou hast said, These two nations and these two countries shall be mine, and we will possess it” (Ezekiel 35:10).

While these prophecies do not predict forced conversion or legal assimilation in explicit terms, they establish a theological pattern: Edom positioning itself to benefit from Judah’s calamity and to lay claim to what God had entrusted to His covenant people. When read alongside the later incorporation of Idumeans into Judaean society and their rise within Jerusalem’s ruling class, these warnings assume striking relevance.

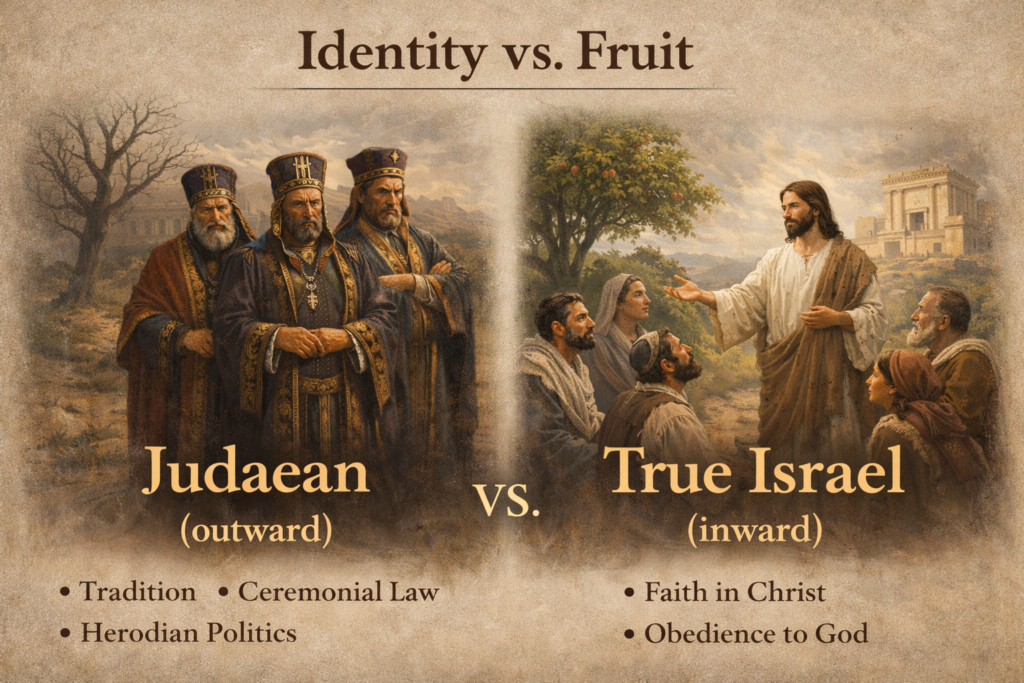

Identity Tested by Fruit, Not Label

By the time of Christ, “Jew” had become a layered and ambiguous designation—geographic, legal, and religious—rather than a reliable indicator of covenant faithfulness. This reality explains why Jesus consistently rejected lineage claims that were not matched by obedience:

“If ye were Abraham’s children, ye would do the works of Abraham” (John 8:39).

The New Testament resolves the tension not by denying Israel’s history, but by redefining true identity through faith. Paul’s conclusion is decisive:

“He is not a Jew, which is one outwardly… But he is a Jew, which is one inwardly” (Romans 2:28–29).

Thus, the convergence of post-exilic intermarriage, Idumean incorporation, and prophetic warning provides essential background for understanding the Jerusalem power structure Jesus confronted—and why Scripture consistently insists that identity before God is ultimately discerned by fruit, not ancestry, geography, or institutional authority.

IV. Jesus and the Judaeans: A Regional Conflict

The Gospels themselves repeatedly emphasize regional hostility, not ethnic condemnation.

John records:

“After these things Jesus walked in Galilee: for he would not walk in Jewry, because the Jews sought to kill him” (John 7:1).

The contrast is explicit:

- Galilee: receptive crowds, common people, disciples

- Judea: ruling elites, hostility, plots of murder

This was not a rejection of “Israelites” as a people, but a confrontation with a corrupt Jerusalem power structure.

When Jesus rebuked the Pharisees and rulers, He did not appeal to ancestry but to spiritual fruit:

- Hypocrisy

- Legalism

- Love of power

- Rejection of truth

These traits—not bloodlines—defined their identity.

V. “Ye Are of Your Father the Devil” (John 8:44)

One of the most controversial statements of Jesus is found in John 8:44. Read through modern assumptions, it appears as an ethnic denunciation. Read within its historical and theological context, it is something else entirely.

Jesus acknowledged their claim to Abrahamic descent (John 8:39) but rejected it based on behavior:

“If ye were Abraham’s children, ye would do the works of Abraham.”

Lineage without obedience is meaningless.

This principle aligns perfectly with the prophetic tradition:

- Esau/Edom opposed Jacob/Israel (Genesis 25:23)

- Edom rejoiced over Judah’s fall (Obadiah 1:10–14)

- Edom became a perpetual symbol of covenant hostility

Jesus’ words identify spiritual fatherhood, not genetic makeup.

VI. Paul’s Clarification: Who Is a Jew?

The Apostle Paul, himself a Benjaminite (Philippians 3:5), resolves the issue decisively:

“For he is not a Jew, which is one outwardly…

But he is a Jew, which is one inwardly; and circumcision is that of the heart” (Romans 2:28–29).

Paul does not redefine Israel away from Scripture—he completes its meaning in Christ. True covenant identity is:

- Not geographic

- Not political

- Not ceremonial

It is spiritual, rooted in faith and obedience.

This harmonizes with:

- Matthew 7:20 (fruit)

- John 1:12–13 (born of God)

- Galatians 3:7, 29 (heirs by faith)

VII. Knowing Them by Their Fruits

Jesus never taught His followers to identify God’s people by labels or lineage. He taught discernment by fruit.

The fruits of the ruling Judaean class included:

- Rejection of the Messiah

- Manipulation of the Law

- Alliance with Rome

- Murder of prophets

The fruits of Christ’s followers included:

- Repentance

- Faith

- Obedience

- Love of truth

These fruits reveal true identity.

Conclusion: Restoring Biblical Clarity

The confusion surrounding the word “Jew” dissolves once its biblical and historical meaning is restored. In the New Testament, Ioudaios primarily denotes Judaean identity, not covenant standing. Jesus’ conflict was not with Israelites as a people, but with a corrupt, often Edomite-influenced establishment that wielded power in Jerusalem. Scripture consistently teaches that God’s people are known not by ancestry or geography, but by faith, obedience, and fruit. True Israel is defined in Christ, not in political or ethnic terms.

The same Scriptures that warn of covenant failure also call God’s people to humility, repentance, and faithfulness. From the prophets to the apostles, identity before God has never been secured by name, lineage, or outward profession, but by obedience flowing from faith. The history surrounding Israel, Judah, and the people later called “Jews” is not preserved merely for academic interest, but as instruction for all who claim the name of God’s people. When these lessons are ignored, error and confusion follow. When they are heeded, Scripture becomes clearer, Christ is magnified, and the assembly of Christ is better guarded against the slow corruption of truth by tradition and power.

As believers today, we must heed Christ’s words:

“Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them.” (Matthew 7:20). The principle in this verse remains as vital now as it was then.

Luke 6:43-45 43 For a good tree bringeth not forth corrupt fruit; neither doth a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit. 44 For every tree is known by his own fruit. For of thorns men do not gather figs, nor of a bramble bush gather they grapes. 45 A good man out of the good treasure of his heart bringeth forth that which is good; and an evil man out of the evil treasure of his heart bringeth forth that which is evil: for of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaketh.

↩ Return to where you were reading

Appendix “A”

In everyday 1st-century usage, the term “Jew” was primarily a geographic andethnic designation. It referred to a person from the territory of Judea, one of the regions of the Roman province, and by extension, an adherent to the religion and customs centered on the Temple in Jerusalem.

However, beneath this surface-level homogeneity, the society was deeply fractured. The term belied a landscape of intense internal division and competing claims to the heritage of Israel. It was not a monolithic group with a single, unified identity.

Here are the key factions that shattered any true homogeneity:

- The Pharisees: The most influential group among the common people. They were zealous for the Oral Law (the Traditions of the Elders) in addition to the Written Torah. They believed in the resurrection of the dead, angels, and spirits. They were the primary opponents of Jesus regarding legalistic interpretations of the Sabbath and purity laws.

- The Sadducees: The aristocratic, priestly ruling class. They controlled the Temple and the Sanhedrin (the high council). They rejected the Oral Law and only accepted the written Torah (the first five books of Moses). They denied the resurrection, the afterlife, and angels. Their power was deeply intertwined with their collaboration with the Roman authorities.

- The Essenes: A separatist, ascetic community (like the one at Qumran that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls). They viewed the Temple priesthood in Jerusalem as corrupt and illegitimate. They lived in tight-knit communities, awaiting a final war between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness.”

- The Zealots: A radical, militant nationalist movement dedicated to the violent overthrow of Roman rule. They believed God alone was their king and that any accommodation with Rome was treason. Their activities eventually sparked the First Jewish-Roman War (AD 66-73).

- The Herodians: A political party that supported the rule of Herod the Great’s dynasty and, by extension, the Roman political order that kept them in power. They were opponents of the Zealots and saw political stability as paramount.

- The Common People (Am Ha’aretz): The vast majority of the population, who were not formal members of any party. They were often looked down upon by the religious elite for their inability to maintain strict ritual purity. This was the primary audience of Jesus’ ministry.

The True “Remnant” and the Re-definition of “Israel”

This is the critical theological shift that occurs in the New Testament. The apostles, following Jesus’ teaching, argue that physical descent from Abraham and a geographic connection to Judea are no longer the defining marks of God’s people.

The term “Jew” begins to be redefined internally and spiritually. The homogeneous ethnic-national identity is superseded by a spiritual one.

- Romans 2:28-29: “For no one is a Jew who is merely one outwardly, nor is circumcision outward and physical. But a Jew is one inwardly, and circumcision is a matter of the heart, by the Spirit, not by the letter.”

- Romans 9:6-8: “For not all who are descended from Israel belong to Israel, and not all are children of Abraham because they are his offspring… This means that it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as offspring.”

- Galatians 3:7, 29: “Know then that it is those of faith who are the sons of Abraham… And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise.”

- Galatians 6:15-16: “For neither circumcision counts for anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creation. And as for all who walk by this rule, peace and mercy be upon them, and upon the Israel of God.” This “Israel of God” is the multi-ethnic community of believers in Christ.

Application to Daniel 9 and Prophecy

When Daniel’s prophecy speaks of “your people” (Daniel 9:24), it is directed at ethnic Israel. The 70-weeks prophecy was about them and their city. Its ultimate purpose, as listed in verse 24, was to deal with their national sin and bring in an everlasting righteousness.

The prophecy was fulfilled in two stages:

- The Atonement (V. 26): The Messiah was “cut off” for the sins of His people, accomplishing atonement. This offer of salvation was made first to the physical descendants of Abraham in Judea.

- The Judgment (V. 26-27): As a nation, the 1st-century Jewish leadership and a majority of the people rejected their Messiah. Therefore, the covenant curses of Deuteronomy 28-29 fell upon them with full force in the form of the Roman armies, who destroyed the city and the sanctuary in AD 70.

This act of judgment marked the definitive end of the Old Covenant system. From that point forward, the homogeneous ethnic meaning of “Jew” was rendered obsolete in the divine economy. God’s people are now defined as the “Israel of God”—the international body of believers, both Gentile and physical Jewish converts, who are united by faith in Jesus Christ. The promises to Abraham are now inherited through faith in the promised “seed,” who is Christ (Galatians 3:16).

Therefore, in a post-AD 70 context, applying the term “Jew” homogeneously to a unified, covenant people of God is a category error. The New Testament presents a clear distinction: there is ethnic Judaism, which persists as a people group, and there is the true, spiritual Israel, Christ’s assembly, which is the heir to the promises.

↩ Return to where you were reading