Introduction: Reclaiming Historical and Theological Clarity

For decades, the claim that the United States was founded upon “Judeo-Christian principles” has been repeated so frequently that it is accepted as historical fact. Yet when examined biblically, historically, and theologically, this notion proves inaccurate. While many of America’s founders personally acknowledged God and drew moral influence from the Christian worldview, the nation’s founding documents themselves do not establish either Christianity or Judaism as its foundation.1

The Declaration of Independence references a “Creator” and “Nature’s God,” affirming that human rights originate from God rather than government.2 This recognition of divine authority reflects a moral awareness consistent with natural law theology. However, the Constitution—which forms the legal structure of the Republic—deliberately avoids endorsing any particular religion, reflecting the founders’ intent to preserve liberty of conscience for all citizens.3

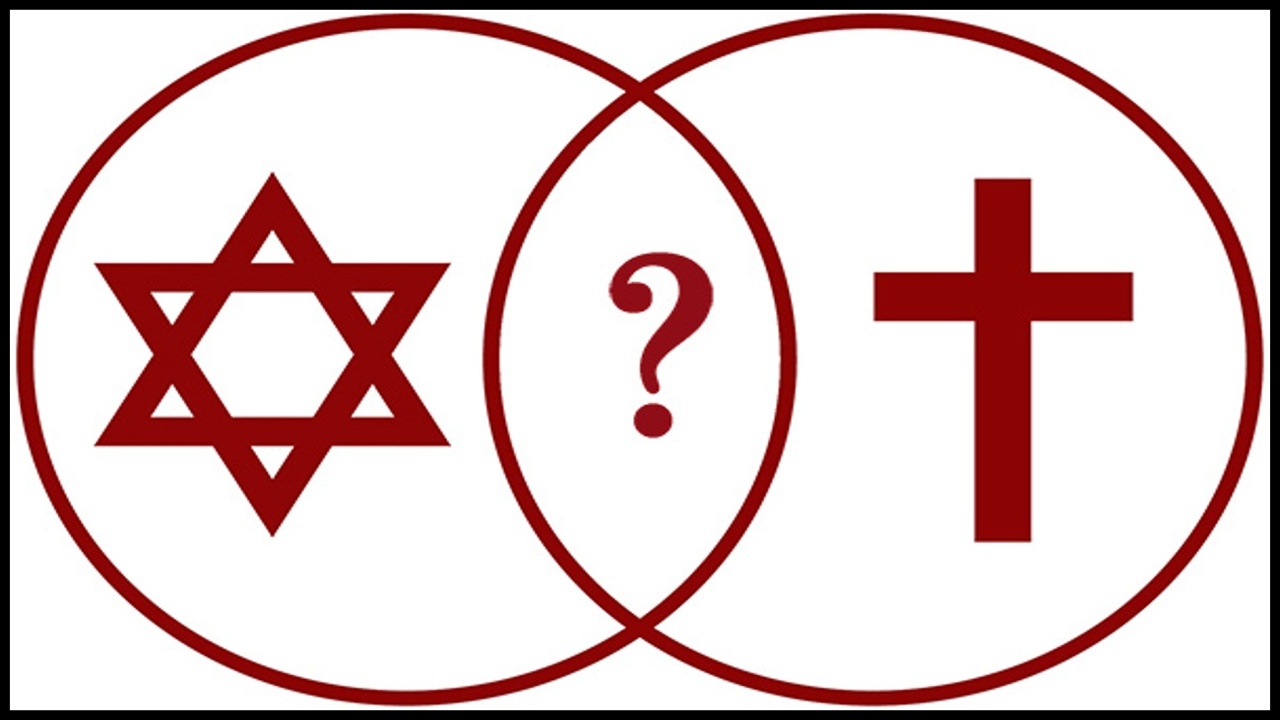

The purpose of this essay is to examine why “Judeo-Christian” is a misleading and ahistorical label and to demonstrate that Judaism and Christianity, though historically related, are theologically incompatible belief systems.

I. The Biblical Divide Between Christianity and Judaism

Christianity rests entirely upon the truth that Jesus Christ is the promised Messiah, the Son of God. Judaism, by contrast, rejects this truth and awaits another. This divergence is not a minor difference in interpretation—it is the defining line between divine revelation and unbelief.

The Apostle John wrote, “He came unto his own, and his own received him not” (John 1:11). He further declared, “Who is a liar but he that denieth that Jesus is the Christ? He is antichrist, that denieth the Father and the Son” (1 John 2:22). To deny Christ is to reject the Father’s testimony.

Paul similarly affirmed, “For Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to every one that believeth” (Romans 10:4). Christianity therefore does not stand beside Judaism—it fulfills what Judaism denies. To unite these two belief systems under one label is to disregard the warning of 2 Corinthians 6:14: “What communion hath light with darkness?”

II. The Old Covenant vs. the Rise of Rabbinic Judaism

The Old Covenant was divine in origin, revealed by God through Moses at Sinai. It was holy, just, and good (Romans 7:12), yet temporary—pointing to the coming of Christ. The religion known today as Judaism, however, is not synonymous with the Old Covenant faith of Israel. After the Babylonian exile (586 B.C.), the people of Judah absorbed various Babylonian customs, linguistic forms, and interpretive traditions.4 These practices, combined with post-exilic commentary, produced what later evolved into Pharisaic Judaism during the Second Temple period.

By the time of Christ, the Pharisees had elevated these human traditions above the written Torah. Jesus condemned this corruption, saying, “For laying aside the commandment of God, ye hold the tradition of men… Full well ye reject the commandment of God, that ye may keep your own tradition” (Mark 7:8–9).

After the destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70, the sacrificial system ended, and the Pharisaic school became the dominant religious authority. Over subsequent centuries, their oral interpretations were codified into the Babylonian Talmud, the central text of what is now called Rabbinic Judaism.5

This transformation marked a decisive break from the Mosaic covenant. The Talmud represents not divine revelation but rabbinic tradition—commentary that often contradicts both the Law and the prophets.6 Thus, modern Judaism is not the Old Covenant faith of Israel; it is a religion born in Babylon, restructured by rabbis, and perpetuated through human tradition. As God foretold through Jeremiah, “Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will make a new covenant… Not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers, which my covenant they brake” (Jeremiah 31:31–32).

III. Christianity: The Fulfillment of the Promise

Christianity is not a continuation of Judaism—it is its divine fulfillment. Jesus declared, “Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfil” (Matthew 5:17). The New Covenant completes what the Old foreshadowed.

The writer of Hebrews affirms, “In that he saith, A new covenant, he hath made the first old” (Hebrews 8:13). The Old Covenant has vanished in the face of the new, eternal covenant sealed in Christ’s blood.

Paul reminds us that the true heirs of Abraham are not defined by bloodline but by faith: “They are not all Israel, which are of Israel… But the children of the promise are counted for the seed” (Romans 9:6–8). Through Christ, believing Jews and Gentiles alike are united into one spiritual body—the true Israel of God (Galatians 6:16).

IV. The Modern Invention of “Judeo-Christian”

The term “Judeo-Christian” is not biblical and did not exist in the 18th century.7 It emerged in the mid-20th century, particularly during the 1930s and 1940s, as a cultural and political expression rather than a theological one.

Historian Mark Silk notes that the term was popularized in America to foster solidarity among Christians and Jews against Nazi ideology and later to define a shared moral stance against atheistic communism.8 This phrase implied a common heritage of ethics and morality, even though the theological foundations of Judaism and Christianity remain utterly distinct.

By blending these two belief systems under one cultural label, mid-century America sought moral unity at the expense of doctrinal truth. The term “Judeo-Christian” thus became part of America’s civil religion—a moral vocabulary detached from biblical covenant theology.9

V. The Founders, the Declaration, and the Constitution

Although the founders never spoke of “Judeo-Christian” principles, many personally affirmed a belief in divine Providence and moral accountability to God. George Washington frequently referred to Providence in his writings and farewell address.10 John Adams famously stated, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”11 Thomas Jefferson, in drafting the Declaration of Independence, appealed to “Nature’s God” and a Creator who endowed mankind with unalienable rights.12

However, the U.S. Constitution—ratified eleven years later—was deliberately written without religious establishment. Article VI prohibits religious tests for public office, and the First Amendment guarantees both the free exercise of religion and freedom from governmental establishment of religion.13

The founders sought a nation governed by moral order under God, not a theocracy. Their design reflected a balance between divine acknowledgment and liberty of conscience—a framework that recognized God as Creator without binding the state to any ecclesiastical authority.

VI. The Theological Incompatibility of “Judeo-Christian” Morality

Although Christianity and Judaism share certain moral precepts (such as prohibitions against theft, murder, and false witness), their sources of authority are irreconcilable. Christianity’s morality flows from spiritual regeneration and obedience to Christ; Judaism’s from rabbinic law and human tradition.

Paul declared that Christ “abolished in his flesh the enmity… to make in himself of twain one new man” (Ephesians 2:15). The dividing wall between Jew and Gentile was removed—not to create a hybrid religion, but to establish a single spiritual body united in Christ.

Therefore, the so-called “Judeo-Christian ethic” is a moral construct, not a theological reality. It merges the fulfilled covenant of Christ with a religious system that rejects Him. Such a union contradicts the gospel itself, which proclaims salvation through grace, not through law.

VII. Conclusion: Truth over Tradition

The assertion that America was founded upon “Judeo-Christian” principles is historically unfounded and theologically misleading. While many of the founders personally acknowledged God, they did not establish a “Christian nation,” nor did they root the Republic in Judaism. The phrase “Judeo-Christian” arose much later as a political and cultural slogan to promote unity and moral conservatism.

More importantly, Judaism and Christianity are not complementary faiths. One awaits a messiah who has already come; the other worships the risen Christ who fulfilled the Law and the Prophets. Modern Judaism, grounded in rabbinic tradition originating from Babylon, is not the faith of Moses but a distortion of it.

As believers, our allegiance must remain with the truth of Scripture, not with cultural labels or civil religion. America may acknowledge a Creator, but salvation is found in Christ alone. As the Lord declared: “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me” (John 14:6).

Appendix: Reference Notes and Source Descriptions

- The Federalist Papers, No. 10; Isaac Kramnick & R. Laurence Moore, The Godless Constitution: The Case Against Religious Correctness (W.W. Norton, 1997). ↩︎

- Declaration of Independence (1776), preamble & paragraph 1 (references to “Nature’s God,” “Creator,” and “divine Providence”). ↩︎

- U.S. Constitution, Article VI (no religious tests) and First Amendment (no establishment; free exercise). ↩︎

- Alfred Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (1883), vol. 1, ch. 2; Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.), “Babylonian Captivity.” ↩︎

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 13, ch. 9; Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 24a; Avodah Zarah 3b. ↩︎

- Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 19, “Talmud,” pp. 1–12; Adin Steinsaltz, The Essential Talmud (Basic Books, 1976). ↩︎

- Oxford English Dictionary, “Judeo-Christian” (earliest usage 1899; widespread adoption 1930s–1940s). ↩︎

- Mark Silk, “Notes on the Judeo-Christian Tradition in America,” American Quarterly 36, no. 1 (Spring 1984): 65–85. ↩︎

- Will Herberg, Protestant, Catholic, Jew: An Essay in American Religious Sociology (Doubleday, 1955). ↩︎

- George Washington, Farewell Address, September 19, 1796 (references to Providence and morality in public life). ↩︎

- John Adams, Address to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts, October 11, 1798 (“Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people…”). ↩︎

- Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence (drafting references to the Creator and Nature’s God), 1776. ↩︎

- U.S. Constitution (1789), Article VI and First Amendment (reiterated to stress legal framework of religious liberty). ↩︎

Author’s Note & Verification Disclaimer

This essay and its accompanying appendix were compiled and formatted with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance readability, citation accuracy, and theological clarity. All scriptural quotations are from the King James Version (KJV). Historical and academic references have been verified against primary or reputable secondary sources, as cited above. The intent is educational and theological, not political. Readers are encouraged to examine each cited work, study the historical context, and “search the scriptures daily, whether those things were so” (Acts 17:11).

© [2025] [Dare To Think]. Compiled with AI assistance and verified historical sources. All rights reserved.